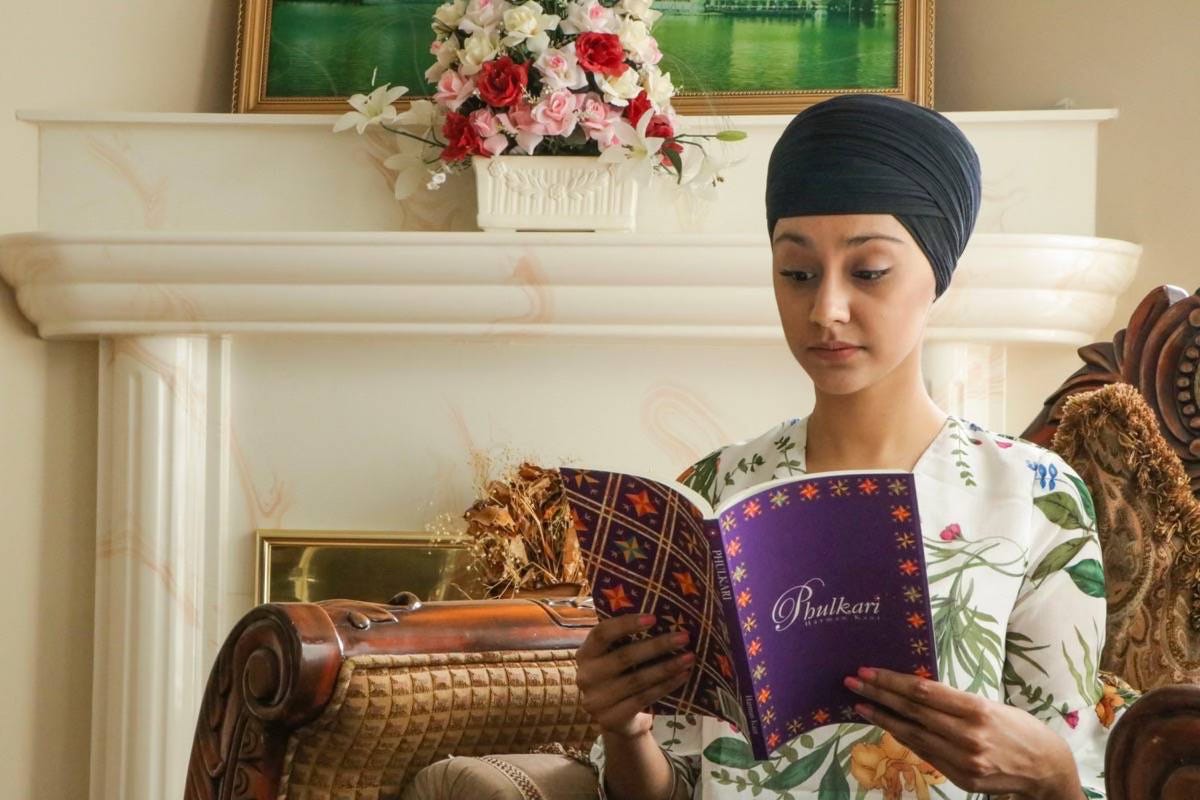

Seven Years of Phulkari: On Outgrowing a Book, and Letting It Live Anyway

May marks seven years since I self-published my debut poetry collection, Phulkari. I was 21 years old, a full-time student, balancing academic deadlines with sleepless nights of editing, formatting, and learning how to self-publish through trial and error. I remember launching that book with more hope than strategy—no team, no agent, no publisher, just a belief that these poems deserved to live in the world.

Seven years later, Phulkari still exists. And I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means for a book to live longer than the version of you who wrote it.

For the past few years, I’ve quietly wrestled with the idea of letting Phulkari go. I’ve considered pulling it from online platforms, taking it off Amazon, making it unavailable for purchase. Part of that came from discomfort—when I read certain poems now, I cringe. There are lines I no longer stand by, ideas I’ve outgrown. I recognize the young woman who wrote them, but I don’t always agree with her anymore.

Some of the poems in Phulkari were written when I was just 15 years old. I’m 28 now. Between then and now, my life has changed in seismic ways. I’ve fallen in love. I’ve gotten married. I’ve left my home country and built a new life elsewhere. I’ve become a mother. I’ve lived through grief, migration, rebirth. And all of those transformations have reshaped the lens through which I view my work.

The person who wrote Phulkari feels like a girl I used to know—earnest, tender, learning how to articulate emotion in the shape of poetry. She was hungry to say something meaningful. She was trying to make sense of her place in the world. And although I can recognize the raw honesty of her voice, I can also see her limitations. Her language was still forming. Her beliefs were still borrowed. She was still unlearning her own biases.

And yet—Phulkari continues to travel. I still receive messages from readers telling me how much it resonated with them, how a line or image gave language to something they had never said out loud. The book is still selling—not just in the U.S. and Canada, but in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands. It has reached places I’ve never been. While I’ve felt ready to move on, Phulkari continues to live in the hands of strangers, who fold its pages, underline its verses, and carry it into their own stories.

And then it hit me: maybe Phulkari is no longer mine. Maybe it never fully was.

I once read that books don’t belong to their authors—they belong to their readers. I don’t get to decide when Phulkari has served its purpose. Just because I’ve moved on doesn’t mean someone else won’t find exactly what they need in its pages.

When I wrote Phulkari, I was intentional in every detail. The title was a metaphor for what I hoped the book would be: a handwoven cloth made of memory, emotion, and inheritance. Each poem was a stitch. Each section was a panel of colour and grief. It was a love letter to my people—to the women who raised me, to the soil that shaped me, to the stories I was raised on.

I chose to self-publish because I didn’t want to compromise the vision. I didn’t want someone to edit or dilute it. I wanted it exactly as I imagined it, even if it was imperfect. And I’m still proud of that choice.

In fact, when I was working on my second collection, Call Me Home, I went back to Phulkari and selected a few poems that still felt true. I included them, mostly unchanged, because they still felt like part of me—like old photographs that hadn’t faded. They were the threads that still held. And in doing that, I realized that it’s okay to carry parts of your past into your present, even as you grow beyond them.

More recently, I’ve been thinking about going back to Phulkari again—not to revise it, but to sit beside it. To annotate it. To meet each poem where it is, and offer reflections from where I am now.

I imagine writing in the margins:

This line no longer feels honest.

This metaphor was inherited, not interrogated.

Here, I was trying to be brave. Here, I was trying to be seen.

There’s something sacred about doing that—not to disown the work, but to be in conversation with it. To treat my younger self with curiosity rather than critique. To honour the girl who wrote those poems, even if I no longer agree with all she believed.

I think we often expect art to be timeless. But some art is a time capsule. Phulkari is that for me. A container of who I was—both the wisdom and the naivety. And just as we would not shame a diary entry for sounding young, maybe I shouldn’t shame my first book for reflecting a younger version of myself.

I’m deeply grateful to be held by such a loving and generous community. I am where I am today because of my people. And maybe that’s why I can’t bring myself to delete the love letter I wrote to them seven years ago.

Yes, I’ve outgrown Phulkari—but that doesn’t make it any less sacred. It feels powerful to look back, to remember where I began, and to see how far I’ve come.

One day, I might feel the same about Call Me Home. And I hope, when that day comes, I’ll return to it with the same softness, the same willingness to listen back to who I was, and say:

You did the best you could with what you knew. Thank you for beginning.

To anyone who picked up Phulkari all those years ago—thank you.

Whether it was your first poetry collection, or your first time seeing yourself in print, or simply something that stayed with you in a quiet moment—I’m so deeply grateful.

If you’ve followed my writing from Phulkari to Call Me Home, thank you for walking with me through every evolution. Thank you for holding space for my voice as it changed, stretched, stumbled, and found new language. Your support is not just something I cherish—it’s something I carry.

And now, a third book is in the works. I’m not yet ready to say too much about it, but I can feel its shape forming. It’s quieter. Maybe more certain. It’s coming from a place I couldn’t have written from before.

Wherever this journey takes me next, I hope you’ll continue to walk beside me.

Thank you for reading. Thank you for remembering. Thank you for staying.

With love, always,

Harman